Final score: Earth 1, Asteroid 0

Nasa’s successful DART mission is reason to celebrate, even if a real threat to Earth is likely to arise on much shorter notice

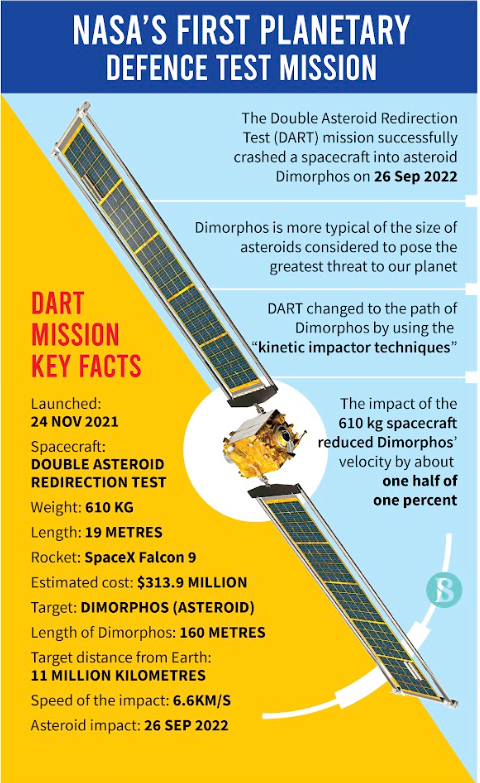

We hit the asteroid. We really hit it. Watching the live feed of the impact, I admit that I tingled. But does the success of the Double Asteroid Redirection Test — DART, for short — mean that the planet is safe from major asteroid strikes?

Not by a long shot. (Sorry.)

Yes, a spacecraft that lifted off 11 months ago to find out whether we could strike and potentially divert an asteroid in outer space performed as designed. It struck Dimorphos, a 170-metre asteroid that's in a binary orbit with the larger Didymos. But as one Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineer said on the live feed immediately after impact, "Now is when the science starts."

In particular, researchers will need time to measure the changes in Dimorphos's orbit, and to correlate them with the extensive theories about the utility of "kinetic impactors" in protecting the planet against asteroid strikes.

Planetary defence, as it's come to be called, has received increasing attention in recent years. Advocates for interception technology tell us that asteroid strikes are the only disaster that we possess the technology to both predict and avoid. Economists argue that it's a public good. Legal scholars suggest that governments possessing the capacity to shoot down asteroids might have a duty under international law to target those headed toward nations unable to protect themselves.

Maybe so. But first we have to prove that the capacity exists.

Which is why the success of the DART mission matters. That we hit the target is a reason to celebrate. But will it work when space debris is actually headed our way? We'll never know for sure until we're forced to try.

Nasa leads a biennial Planetary Defence Conference Exercise, which brings agencies from around the world together to prevent a simulated asteroid strike. In the 2019 version, scientists were tasked with deflecting an asteroid heading for Denver. They succeeded, by hitting it with six "kinetic impactors" (like DART) — only to discover, to their dismay, that the impact sheared off a large chunk that would strike Manhattan with 1,000 times the energy of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The simulated disaster was hardly a first. In past exercises, we've lost Dhaka and the French Riviera. In 2019, we'd have lost Tokyo too, but the participants used simulated nuclear weapons to destroy the simulated threat. (In the 2021 version, politics got in the way of this solution.)

Hollywood loves hurtling extinction-level objects toward earth, and the results can be great popcorn movies. But the risk far more likely to materialise involves "smaller" asteroids like the one that exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013 with a force of over 400 kilotons — more than 20 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb.

The Chelyabinsk asteroid was only about 20 metres in diameter, and its impact wasn't predicted. What's the annual probability that an object this size will intercept the Earth? Most calculations suggest that the likelihood is small, but nobody really knows.

For one thing, predicting the long-term paths of less-than-moon-sized bodies presents enormous difficulty. (We didn't even have high-resolution images of Dimorphos until minutes before impact.) For another, though only 500 or so small asteroids in orbits near ours have been catalogued, researchers estimate that the true number is well up in the millions. On the plus side, this is precisely the range where we can expect kinetic impacts to do the most good, even with short warning.

If we can hit them.

Which it now seems we can — but!

The DART mission cost over $300 million, and involved sending a spacecraft 34 million miles to strike an asteroid whose motion is well understood. We had, in effect, all the time in the world to plan the experiment and carry it out.

When the real-life threat arises — and it will — we don't know how much time we'll have. Although we'd likely have years of warning for larger asteroids, with the smaller ones the time involved might be weeks or days. If we're serious about planetary defence, we'll need interceptors, plural, ready to go.

And eventually we'll face a large asteroid. Maybe not as big as the meteor (possibly a comet) estimated at 50 metres that exploded over Tunguska, Russia, in 1908, with a force of 10 megatons; but a 20-metre asteroid would destroy most of a fair-sized city. That's why we have to learn how to nudge.

Nasa's biennial simulations remind us that no matter how easily a rogue asteroid is blown to pieces in the nick of time in the movies, in the real universe the threatening asteroid often must be met early or not at all. The earlier the kinetic impact, the more easily the object can be deflected. The 2019 simulation posited an asteroid that began with a 1% chance of striking the earth in eight years. As fictional years passed, the probability grew. Eventually it reached 100%. If the world's (simulated) space agencies had waited to act until the threat was certain, they would have acted too late.

Supporters of space exploration like to argue that everyone benefits. At times, they're expressing the techno-optimism that supplies the premise for the Apple+ hit "For All Mankind" — a show bold enough to suggest that if humans had been wise enough to keep going to the moon, we'd have had both cell phones and a female president by the 1990s.

But forget optimism. We can also support space exploration for entirely reasons related to the survival of the species: We're going to need the technical knowledge that the space program generates. Because the day will come, in a century or three, when a huge celestial object will hurtle our way. If the human race hopes to survive when that happens, now is the time to be practising.

Disclaimer: This article first appeared on Bloomberg, and is published by special syndication arrangement.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel