What explains exports decline

The trade diversion effects seem to have bypassed Bangladesh. On the contrary it may have had some perverse effects

Bangladesh's exports this fiscal year have had an ominous start. After a very promising 8.6 percent growth in July, export decline accelerated in the next four months, resulting in 7.6 percent cumulative decline in the first five months of FY20.

Readymade garments and non-garments exports have declined by 7.7 percent and 6.9 percent respectively. Raw jute, jute goods, tea, pharmaceuticals and other chemicals are the only exceptions with positive growth so far, but these together accounted for only 3.1 percent of total exports. Exports to the US declined by 5 percent and to the EU by 8 percent. India has been the only exception where Bangladesh's exports grew by 0.8 percent, but India accounted for only 3.6 percent of the total exports in the first five months.

What accounts for such worrisome decline?

Decline in demand growth globally. The US-China trade war is starting to have effects on the broader health of the global economy. Data at the end of July showed the euro zone — the 19-member region that shares the euro — growing at a rate of just 0.2 percent in the second quarter, down from a rate of 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2019. The US economy grew at an annualized rate of 2.1 percent in the second quarter of the year, 1 percentage point lower than in the previous quarter. The threat of more tariffs and a trade war itself has dampening impact on business. Demand weaknesses are also evident from the 2.6 percent decline in imports in the European Union (EU) and 1.4 percent decline in imports in the US in July-September 2019 relative to the same period the previous year, according to World Trade Organization data.

Weak demand could have contributed to the 1.9 percent and 1.2 percent decline in prices of cotton T-shirt and cotton trousers (male) in October 2019, as recently reported by the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA). Prices of other garment items also declined, but those two accounts for nearly 34 percent of RMG exports. Weak demand and falling prices cannot be the full story. If it were, Bangladesh's competitors would also have experienced decline in export earnings. They did not. According to BGMEA report, export growth in July-August registered by Vietnam was 10.5 percent, Pakistan 4.7 percent and India 2.25 percent.

The diversion of trade diversion. The trade diversion effects seem to have bypassed Bangladesh. On the contrary, it may have had some perverse effects. The trade diversion effects – increased imports from countries not directly involved in the trade war – for the first half of 2019 is estimated at about $21 billion (UNCTAD 2019), bringing substantial benefits for Taiwan (province of China), Mexico, Vietnam and the European Union. Trade diversion effects show considerable variance both across countries and sectors. Large countries with spare supply capacity and available trade infrastructure were the ones better positioned to replace China in the United States market. Trade agreements as well as geography also appear to be playing a significant role. Bangladesh is well behind competitors on all these counts.

European companies are benefitting from the exodus of their US counterparts from China and are taking advantage of the capacity becoming available as competition between Chinese suppliers heats up. This may explain, at least in part, why Bangladesh's exports to the EU has declined. The good news is that it is unlikely to be more than a blip, as Chinese manufacturers have little room for further improvements in efficiency and will not be able to finance price-driven competition for long.

High sourcing costs. The US tariff action against China has increased sourcing costs. It is pushing up the price of US apparel imports across the board. According to the McKinsey Apparel CPO Survey 2019, the costs to source in the main alternatives to China – especially Vietnam, Bangladesh and India – are soaring. And the uncertainty seems to also affect logistics and transportation costs. As companies are moving sourcing orders to Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India, the average price of US apparel imports from these countries – the main alternatives to China – have all gone up by more than 20 percent in 2019 (January-May) year on year. Bangladesh appears to have lost out due to high lead times resulting from regulatory complexity and unpredictability in trading across borders. Bangladesh ranked 176 out of 190 countries on this indicator in the World Bank's Doing Business 2020 while Vietnam ranked 104, India 68 and Pakistan 111.

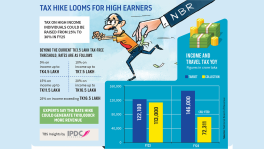

Loss of price competitiveness. The taka-US dollar rate depreciated moderately while the real effective exchange rate (REER) appreciated by 5.6 percent in FY19, according to the World Bank's Bangladesh Development Update (October 2019). The taka appreciated against the euro from Tk 97.78 to 94.77 and the pound sterling from Tk 110.36 to 107.51 over the same period. Exchange rate interventions kept the inter-bank exchange rate within a narrow Tk 83-85 per US$ range over the past two years, leading to the appreciation of taka against the currencies of other important trading partner currencies. The consequent appreciation in the REER led to a loss of price competitiveness internationally, particularly when combined with relatively high inflation.

What can be done to stem the decline?

History provides reasons for some optimism. In FY08, exports declined 21.1 percent in July and remained in the negative territory until October but ended the fiscal year with 15.9 percent growth as both garment and non-garment exports recovered rapidly in the last half of the fiscal year. Again, in FY10, export growth had been in the negative in the first three quarters, but the year ended with 4.1 percent growth, driven primarily by recovery in non-garment exports.

Whether or not history will repeat itself depends on global recovery which in turn depends on the dissipation of trade tensions between the world's two largest economies – the US and China. Both sides appeared close to reaching a phased agreement by the end of this year, but earlier this week, Trump's mood swung once again towards waiting until after the November 2020 US presidential election to strike a trade deal with China.

Efforts to diversify exports need a major shift in gear. Vietnam has managed the biggest gains despite weakening global economy because its exports are not only in textiles, but in several other sectors ranging from seafood to semiconductors in which the US levied tariffs on their Chinese counterparts. In the first four months of this year, US imports of mobile phones from Vietnam more than doubled year-on-year, while imports from China contracted by 27 percent, according to data from the United States International Trade Commission (USITC). Over the same period, US computer imports from Vietnam rose by 79 percent, against a 13 percent drop in Chinese imports. US imports of fish from Vietnam rose by more than 40 percent in the first four months of this year, while imports from China fell. According to McKinsey 2019, a record high percentage of respondents (80 percent) expressed interest in expanding sourcing from Bangladesh in the next two years because of price advantages. However, respondents still found Bangladesh not as attractive as many of its competitors regarding speed to market, flexibility & agility, and risk of compliance.

Diversification requires tariff liberalization, shorter lead times, competitive exchange rate and better market access. Tariff liberalization alone cannot trigger large supply responses because of a number of supply-side constraints and the lack of an environment enabling entrepreneurship and innovation. High lead-time is the biggest challenge owing to messy regulations governing the administration of the existing incentive regime for export diversification, inefficiencies at ports and related internal road transportation. Greater flexibility in exchange rate will help keep up with the close competitors. Diversification also requires better market access by having bilateral free trade agreements and joining multilateral arrangements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Indonesia, Korea, the Philippines, Thailand and Taiwan have expressed interest in joining the CPTPP, and China is currently studying the possibility of membership. If these countries can do it, why can't Bangladesh?

The author is an economist.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel