Addressing the Fiscal Conundrum in Bangladesh

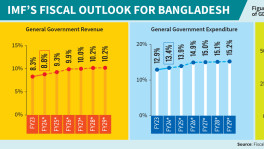

Riding on the back of solid development progress of the past 50 years since independence, Bangladesh policy makers are emboldened to aspire high. In 2020 the government adopted the Bangladesh Perspective Plan 2021-2041 (PP2041) that seeks to achieve Upper Middle-Income Country (UMIC) status and eliminate extreme poverty by 2031. These are worthy but highly ambitious targets. The PP2041 recognizes the need for major policy and institutional reforms to secure these targets. A core policy reform is tax revenue mobilization, which has turned out to be the Achilles Heel of Bangladesh development strategy. The medium-term fiscal framework adopted by PP2041 and reflected in the 8th Five-Year Plan (8FYP) seeks to raise the tax-to-GDP ratio to 12.3% by FY2025 and 17.4% by FY2031. As compared to these targets, actual tax revenue was a mere 7.8% of GDP in FY2022.

The fiscal conundrum is illustrated in Table 1. At around 15% of GDP, Bangladesh total public spending is amongst the lowest in the world. Once fixed spending commitments on civil service wages, pensions, materials, interest cost of public debt and transfers to local government institutions (LGIs) and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are taken into account (7.2% of GDP), only 7.7% of GDP is left for financing other spending including core spending on infrastructure, education, health, water, agriculture and social protection. On top, subsidy spending takes away a substantial share (1.5% of GDP), leaving a mere 6.2% of GDP for development spending.

The financing challenges in health, education, agriculture, water, infrastructure and social protection are immense. Trying to address these needs with a mere 6.2% of GDP is mind boggling. It is no wonder that critical public spending in all these core development areas is grossly inadequate. This public spending constraint alone would jeopardize the country's ability to secure the development targets of the PP2041.

The fiscal problem has simmered and grown over a long period of time. Progress has been slow and halting (Table 1). In 2009, when the current government came to power, it inherited a pretty dismal fiscal picture. Total public spending was a mere 10.4% of GDP and investment spending was only 3.0% of GDP. Over the past 13 years, some progress was made to upgrade the public spending and public investment efforts, increasing by 4.5% and 3.2% of GDP respectively. This is a positive development, but remains highly inadequate relative to needs and especially in the context of the PP2041 targets.

For example, the ability to eradicate extreme poverty by 2031 will require massive investment in human capital (health and education) and social protection (total social sector spending). Yet, at a mere 3.2% of GDP, total social sector spending is amongst the lowest in the developing world. The gap in total social sector spending between selected UMI and LMI countries and Bangladesh illustrates the fiscal challenge (Figure 1).

Importantly, the fiscal structure has not improved much. Government savings are negligible (unchanged at 0.1% of GDP since FY2009) and 95-98% of the investment spending is financed through public borrowings. The low level of public investment spending along with the growing reliance on deficit financing speaks volumes about the poor state of the domestic resource mobilization effort.

The main reason for this low public spending effort on development is the inability to mobilize adequate tax revenues (Figure 2). The 3.2% of GDP increase in public investment was entirely funded through an increase in fiscal deficit from 2.8% of GDP in FY2009 to 6.1% of GDP in FY2022. The tax effort has increased marginally, from 6.5% of GDP in FY2009 to 7.8% of GDP in FY2022, which was barely enough to finance the growing fixed cost needs of the budget, thereby leaving no surplus to finance development needs.

The government made numerous attempts to strengthen the tax system. The most serious effort was the adoption of the Tax Modernization Plan in FY2011, which showed promising signs. The tax to GDP ratio increased by 1.3% of GDP between FY2009 and FY2012. But the effort proved short-lived as it was abandoned after FY2012 owing to political pressures from vested interest. The modernization of the VAT was approved by the Parliament in 2012 but never implemented in its original form. Since then, no serious tax reform program was developed. Each year during the budget season the government makes some vain efforts to improve revenue performance through a range of unfocused and administrative interventions, mostly concentrated on selected enterprises (tobacco, banking and trade tariffs) and other ad-hoc interventions. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, these efforts have not yielded much improvement in tax performance since the tax revenue targets were not based on proper tax planning and policy reforms.

The ineffectiveness of the tax effort is illustrated in Figure 2. Actual tax revenues since FY2014 have been diverging significantly from the bloated tax targets in the budget, reaching a peak in FY2020, when the gap between the actual and the budget tax target reached 3.7% of GDP (a shortfall of 35%). Fortunately, these futile attempts to chase fictitious tax targets are now being corrected and the gap between actual and budget tax targets has been reduced to single digits. This realism in budget making is a positive development. Yet, the weak tax performance remains a major development constraint.

At a mere 7.8% of GDP, the tax effort in Bangladesh remains amongst the lowest in the world (Figure 3). Without a major upgrading of tax performance, Bangladesh will not likely achieve its PP2041 development targets.

The tax reform agenda moving forward is substantial. Much research has been done on required tax reforms and the findings shared with the government. Tax reform implementation is a political economy challenge. Reforms entail a major overhaul of the entire tax planning, policy and administrative system including the separation of tax planning and policy from tax collection, full digitization of the tax administration system, arms- length relationship between tax payers and tax collectors that precludes all types of negotiated and personalized tax settlements unwarranted under the tax laws, simplification of the tax laws and the tax filing process, doing away with income-expenditure reconciliation, incentives for voluntary tax compliance with self-assessment, highly selective and productive audits, adoption of the original 2012 VAT Law, rationalization of the trade tax system to eliminate the anti-export bias, proper tax treatment of all types of capital gains, the introduction of a modern property tax system to invigorate the financial autonomy of the LGIs, and the conversion of the NBR from a tax police department to a tax service agency.

Given the magnitude of the tax reform agenda and to avoid conflict of interest, it might be useful to establish a Tax Modernization Expert Group comprising of representatives from the well-established academia/ research community, top business houses, and senior retired civil servants with experience in tax administration. The report should be time-bound and submitted to the ECNEC for approval and implementation. India, for example, has benefited from the recommendations of several rounds of Tax Reform Commissions.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel